A lot of existing technology will never be useful to retailers because it won’t give customers a better experience. Simple enough.

Except retailers — including retail giants — continue to roll out new tech-forward features that flop.

New tech is exciting, and the digital landscape holds an abundance of promise for retailers, so how can you tell whether a new feature will work or it’s just an exciting technological advancement that won’t pay off for retail?

- It is accessible to the majority of users.

- It offers a long-term benefit to users that outweighs any costs.

- It enhances or enables organic user behaviors.

If a new feature or technological solution has these three elements, it will be more likely to appeal to consumers and be useful for the long term. Therefore, developing these tech features is a good investment because the customers who use them will be more delighted with your customer experience.

Accessibility is the groundwork for any new feature

Technology moves exceptionally fast — so fast that the possibilities of the tech sometimes outpace the people who can benefit from it. It’s exciting, but the novelty of a technological advancement is less important than its practicality for consumers.

Think about virtual reality. It’s been hyped for years:

- Facebook bought Oculus for $2 billion in 2014, which sparked a big discussion about the future of virtual gaming, VR training, and more.

- In 2015, Business Insider declared that it would be at least five years until VR was ready for the masses.

- In 2016, The Wall Street Journal said that the hype train for VR was about to crash.

- In 2017, The Economist gave VR a “reality check” that was not as positive as the 2014 hype would have predicted.

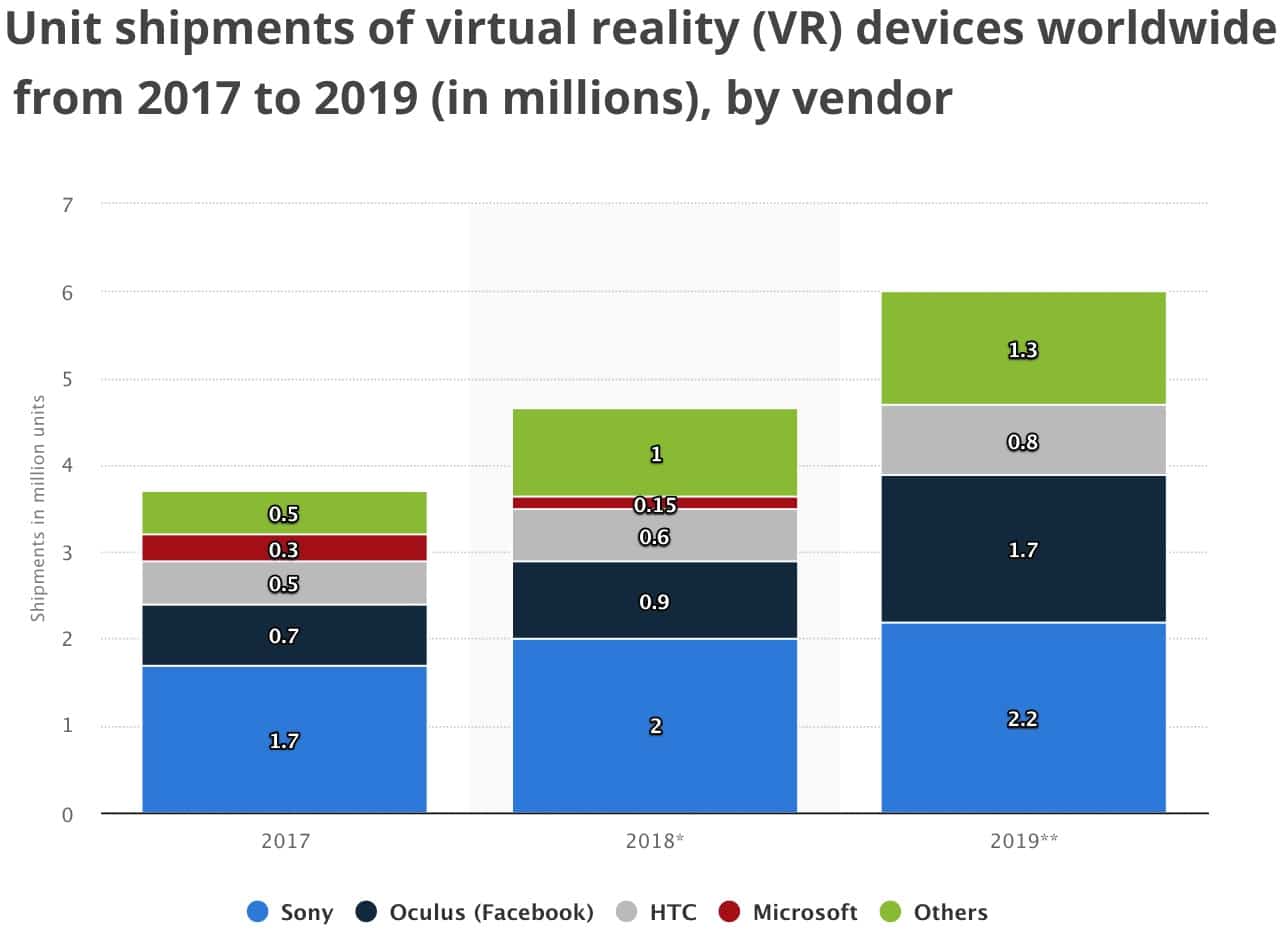

In fact, until 2018, Facebook was struggling to break a million VR units shipped, and Digital Trends reported that numbers across the industry were poor.

[

Source]

Companies that envisioned a bright future for VR — especially gaming VR — haven’t seen a payoff. Part of the problem is that the tech requires more upstart and more money than other systems. It might be worth it for a gamer to purchase a VR system instead of a new Xbox (although customer purchases indicate they won’t), but it’s not worth it for someone who is looking for an easier shopping experience.

The hype around VR supposed that it would touch every single part of our lives and that we would all be clamoring for a slice. But the cost is still greater than the benefit years after the hype train left the station. It’s not an accessible addition to retail strategy, specialized trainings, sports franchises, or television executives because it’s not in the hands of consumers, and it’s too precious and expensive to get there.

What’s already in the hands of consumers? A cell phone. That’s why AR is doing much better than VR. Beyond Pokemon Go’s success, retailers can easily tap into AR developments because they rely on a piece of equipment that many consumers already have.

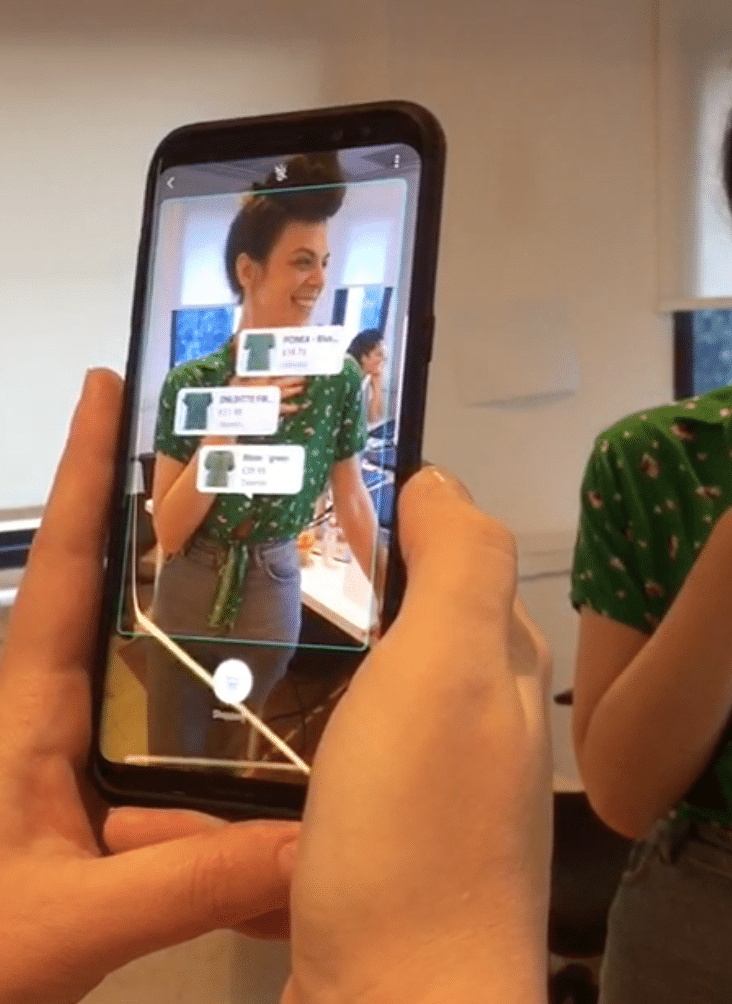

Take visual search for example. If anyone with a cell phone can take a picture of their friend’s outfit and immediately see shopping options for that outfit, that’s accessible AR working for a retailer. No new tech, no new purchases — just a phone camera. Below is an example of this happening during a demonstration of Samsung’s Bixby:

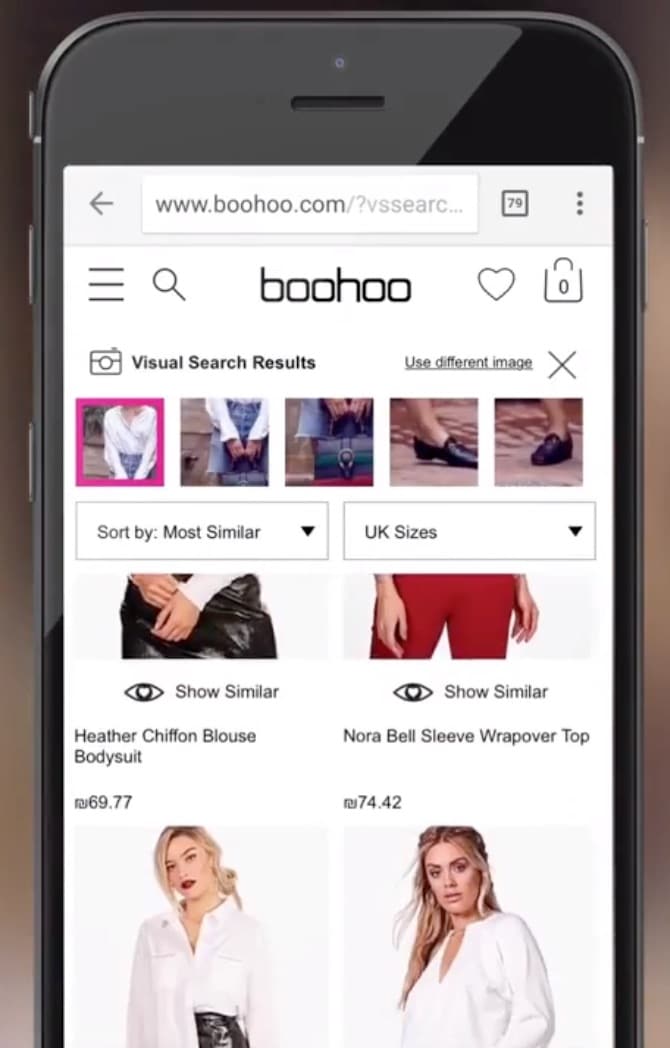

Retailers can take advantage of this technology by adding a camera button to their online stores like Boohoo has. A user takes or uploads a photo, and their visual search results contain the shirt, skirt, bag, and shoes pictured, instantly:

Users can point, shoot, and shop. While VR has incredible possibilities — ones that have led to incredible hype — AR is succeeding for retail and other industries because it’s already accessible to users.

Benefits must be long term, and costs must be low

Humans, psychologically speaking, are creatures of habit — we resist change. Unfortunately, this can be a roadblock for companies looking to make use of technological advances to appeal to consumers in retail. In order for a tech feature to appeal to customers, its benefits must be great enough to push through their resistance to change, and the costs must be low. Otherwise, the feature will see little adoption, even if it adequately solves a customer problem.

A famously bad example of this is Amazon Key. Customers’ packages were being stolen from their front porches between the time they were dropped off and the time customers returned home. Amazon used technological advances in the cloud, mobile device streaming, and digital locks to solve the problem. With Amazon Key, delivery people could get access to people’s homes and leave packages inside.

The Washington Post had their tech reporter demo the service, with Amazon delivery people leaving packages in his front hall. [Source]

This innovation was solving a customer problem with tech that wasn’t available for consumers until the last decade and could have been exciting. Instead, it was widely labeled as creepy, with commenters saying things like, “I’d rather have porch pirates steal my sponges than let Amazon in my house.” To make matters worse, the tech didn’t work as well as it could have, and if you wanted to keep your home’s security system on or if your dog barked at the delivery person/intruder, your boxes ended up on your front porch anyway.

What Amazon offered was a novel technological solution to an increasingly common — and costly — problem. But what consumers experienced were minimal benefits and an invasive change from their normal home security routines. The benefits were too low and the costs too high.

So Amazon went back to the drawing board and created a relatively low-tech solution called Amazon Day, which allows Prime members to choose a day of the week they want their Amazon purchases to arrive. It helps ensure the safety of their packages simply by giving the customer more control over the delivery time.

It’s not a sexy feature, but it offers only benefits for users, with virtually no cost. And while the tech behind Amazon Key is undoubtedly more exciting than the tech behind Amazon Day, the latter ultimately works better.

Features must enhance organic user behaviors

Organic behaviors happen when humans are let loose on technology. Yes, we may learn where a menu is or how to use hot-key commands, but successful technology enhances the way that we want to do things.

Take word processing, for example. Sure, there are bells and whistles. But humans have always written things down, copied their texts, shared them, and used different stylization, like underlining. Word processing software is a huge success because they allow us to do these “organic behaviors” faster and better than ever before. Yes, we needed to learn which button to press to start a bulleted list or copy and paste, but these were facilitating actions we wanted to take, actions that fell in line with hundreds of years of writing lists and copying by hand.

A great example of a “word processor” of retail is smart mirrors in dressing rooms. What do people do in dressing rooms? They assess size and fit. They think about what other pieces would go with the clothes they’re trying on. They ask for more options or additional items to create an outfit, and they think about their budget.

A smart mirror can “see” someone standing in front of it and show that person items similar to those they’re trying on, suggest additions to the outfit, and help customers request additional help or sizes. An immersive digital experience with a smart dressing room mirror means a customer can sign into their account and save their look for later if it’s not in the budget until next month, or, if it is, they can buy the items right then and there. Smart mirrors enhance the organic actions that customers want to take in a dressing room in a natural way.

On the other hand, forcing customers to use novel tech can backfire if it doesn’t relate to how they interact with a product. Take fast-food franchises and their mobile apps. Apps are an amazing technological advancement. They completely changed the way we were able to use our phones. But are they what fast-food users want?

Fast food is, by nature, very quick. Apps are unlikely to significantly cut down on the time one spends waiting for food, especially at drive-thrus. Menus are standardized and don’t change frequently, so they’re not something a user needs to frequently check or browse.

The one thing a fast-food user seems to want an app for is discounts. Apptopia dove into fast-food app downloads and saw that when a company introduced a price-related promotion from their app, downloads spiked:

Companies started putting on these promotions because they wanted their apps on people’s phones, and they weren’t seeing the numbers they wanted. But Apptopia hasn’t been able to find evidence of long-term success for these companies in terms of active app users, just spikes in downloads with a promotion.

That’s probably partially because fast-food eaters — like most of us — love to get a discount but don’t necessarily need to have Dairy Queen available on their phone 24/7. Even though apps are a great innovation, they don’t speak to the organic behaviors of the fast-food consumer.

Think about users first and features second

No matter what sector of retail or ecommerce you’re in, consumers have to be top of mind. Tech must come second because it won’t work without consumer engagement. If you want to build a new, exciting feature, be discerning and ask yourself, “Is this an accessible feature that adds value and enhances my customer’s experience?” Then ask it again. Don’t let new and shiny distract from good decision-making. Creating the innovations and features that matter most to consumers will happen only when companies put these questions at the forefront of innovation. Then, everyone will reap technology’s rewards.