From a consumer perspective, automatic photo tagging may not seem like a revolution, but for companies it’s a much bigger fish than it may appear. Automatic photo tagging and other image technology typically develop as a secondary aspect of a business’s services because it’s not as quick-to-market as things that rely on text, even when it’s a better solution.

We saw this firsthand in the history of image search, an obvious solution to an obvious problem with text search — that people aren’t good at describing images in the same way that machines categorize them. But even though searching based on an image would seem like a no-brainer to implement, the development of those tools came slower than text-only search.

For companies using automatic photo tagging, this is much the same. Facebook, Flickr, iPhoto, Pinterest, ecommerce sites, iOS, cloud photo sharing apps — they all have a reason to develop automatic photo tagging: because it makes things easier for consumers. So why are we just seeing a big push in the automatic photo tagging space, and what can we expect now that automatic photo tagging tech is finally heating up?

In the first part of this series, we’ll explore the first half of that question, starting from the place many of us first encountered consumer-side automatic photo tagging: Facebook.

Speed, power and innovation: automatic photo tagging appears for consumers

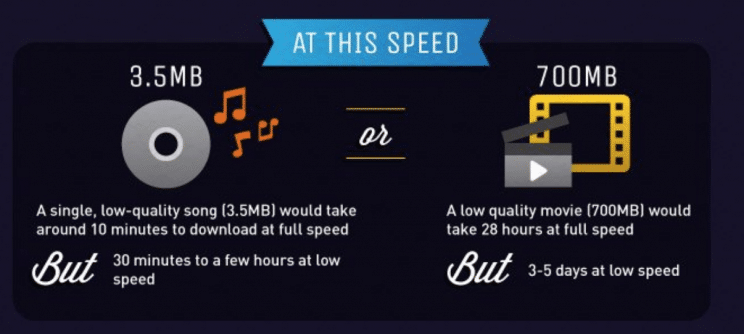

One of the single biggest factors in how much we use the internet now and how useful of a tool it is is speed. In 1993 with an optimal dial-up connection, it would take a user 28 hours to load a 700 MB movie. The internet was awash with possibilities, but the transfer of information was so slow that anything other than text was prohibitive.

Things got better. Dial-up started to phase out for the most-connected consumers in the 00s, and the appetite for images, sound and video possibilities started to blossom. YouTube was founded in 2005 and was serving 100 million views per day in July of 2006. Broadband was booming, and uploading, downloading and viewing image content was fast enough that people actually wanted to do it.

[

Source]

This coincided with a rise in social media, YouTube aside. Facebook, a soon-to-be-ubiquitous website, started seeing huge growth in the number of photos uploaded. By February of 2010, they moved to 3 billion photos uploaded a month, up from 1 billion images uploaded per month in July 2009. And if anyone had a clear-cut use case for automatic photo tagging, it was them.

Taking Control Of Images: Automation Evolves

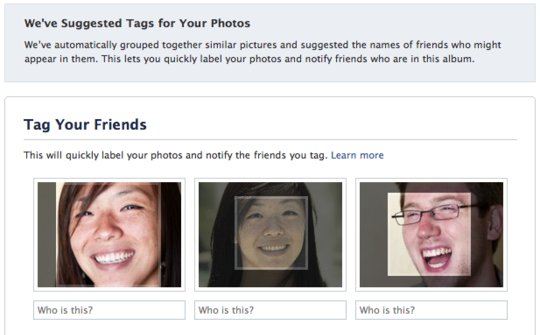

In December 2010, Facebook rolled out facial recognition to photo tagging after starting testing in July. Those on the service at the time will remember the novelty of seeing suggested friends when you uploaded a photo. Although this is a common experience now, it was the first time that many people were seeing automation technology for images in their daily lives.

Facebook saw it as a way to take out part of the pain of uploading photos on the service — tagging photos, and later knowing what photos of you had been uploaded, even if they weren’t tagged.

[

Source]

“Now if you upload pictures from your cousin’s wedding, we’ll group together pictures of the bride and suggest her name. Instead of typing her name 64 times, all you’ll need to do is click ‘Save’ […] We notify you when you’re tagged, and you can untag yourself at any time. As always, only friends can tag each other in photos,” the company wrote.

There was an opt-out for the feature, a nod to the fact that some people were uncomfortable with the thought that a company would be able to automatically identify them — this we’ll come back to later.

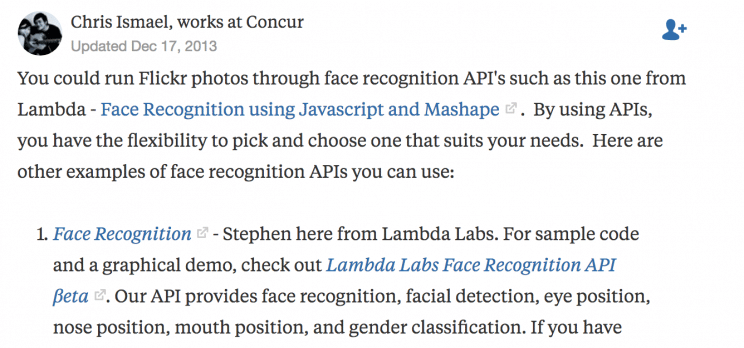

As Facebook was implementing this tech, consumers and corporations were scrambling for ways to provide similar solutions to problems finding and organizing photos on other platforms. Take the Quora question “Is there any working face recognition for Flickr?” — at the time of asking, the answer was no. But a responder did not hesitate to list out every possible 2013 workaround to this problem. Fifty-five solutions were offered in total:

This answer illustrates the fact that there were people working on automatic tagging and recognition features left and right. But corporations were still trying to figure out the solutions that would allow them to bring the best image tech to consumers and were not expedient in rolling it out.

In that same year, lucky for that Quora asker, Yahoo, who owned Flickr, acquired IQ Engines to try to add automatic tagging and sorting to their image properties — arguably a bigger task for a completely image-based platform than for Facebook, who had a fraction of the applicable use cases.

The basics were in place. Players were starting to get set. And when the ball got rolling, it picked up momentum fast.

Caught in the middle: missteps and momentum

As basic provisions were rolling out to consumers, companies were working to realize the full potential of automatic tagging and recognition. Images in and of themselves are full of data and information.

It has always been a matter of how we can get computers to process the data that has been a limiting factor on what we can do with them. And companies knew that pushing the envelope on our ability to recognize, manipulate and categorize images would shoot forward what they could do internally and what they could offer consumers.

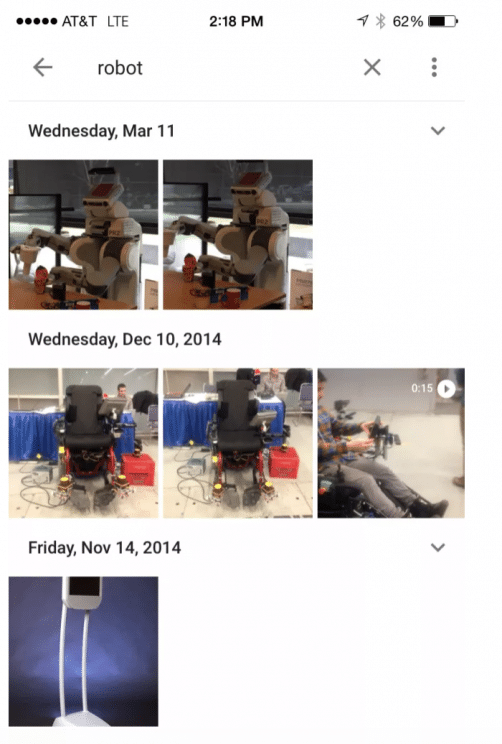

By 2015, Google was deep into mining photos for data — unsurprising given their image search index. But things were different this time, because Google wasn’t using their technology on someone else’s photo on the web but on your photos that you uploaded. A Splinter piece reported that Google was “disturbingly good” at this, offering:

“You can look for photos with “dogs” in them, “skiing,” “bridges,” or “parties.” In case you don’t know what to search, Google offers help, pre-categorizing your photos. When you click on the magnifying glass in the app, Google offers up categories for you: “People” (with photos of each of the people it’s picked out from your collection); “Places” (based on geolocation information in the photos); and “Things” (separated into categories it’s discerned, like “food,” “cars,” “beaches,” and “monuments”).”

An extension of the lukewarm Google+, Google Photos was a natural move for the company. Consumers knew and trusted Google and were already using their image search and their Google Drive services. Hosting personal photos fit — but it was an uncomfortable growth.

An early example of Google’s technology returns a user’s search for “Robot” to varying degrees of success. | Source

Despite the fact that Google and other companies had clearly been working on this technology far before they rolled it out to consumers, they failed to keep themselves out of hot water.

In July 2015 — that very same year — Google had to apologize after its new photo app labeled two black people as “gorillas.” This would have been more surprising had Flickr not had a near-identical problem in May of that year. Filckr described their technology as “advanced image recognition” that automatically categorized photos into broad groups, but the sensitivity wasn’t there.

These companies were rightfully chastised for their lack of foresight as to how their “new” technology could behave. In the rush to bring solutions to consumers, racist missteps started to show a darker underside to what would happen if corporations weren’t careful.

Hitting The Breaks

It would not be fair to say that companies stopped working on automatic photo tagging in the wake of these incidents, but it would be fair to say things cooled down a little. Consumers had mostly embraced Facebook’s novel technology in 2010, but by 2015 it wasn’t exciting enough to push itself past missteps from sheer momentum alone.

For consumers, use cases were broad, non-specific and more interested in showing the raw potential and solving small-scale problems (like searching personal photos in existing apps) than pushing an industry or consumer experience ahead.

And the technology was also a huge blank space in our reality. Sure, we had had sci-fi movies aplenty that offered futuristic ideas of what could happen, but there was an uneasiness about what was being developed.

A report by The New York Times as early as 2011 brought up questions of anonymity in public life — questions we still haven’t answered. In 2014 the FBI announced that their “next generation” identification system was fully operational, and The Guardian followed up with fears a year later, calling it a “privacy nightmare” and urging EU lawmakers to be proactive about legislation.

The heading image from a speculative New York Times’ report showcased billboard technology that detected faces and displayed ads that corresponded to their categorizations (young, female). | Source

Consumers and corporations were starting to understand just how powerful image technologies could be, just how much they could shape the cultural narrative, but the sensitivity and the technology were nowhere near their full potential.

And where was the benefit to consumers in all of this? The rich, incredible technology that was being developed had an absolutely enormous upside for consumers that had nothing to do with being tracked down by law enforcement or sci-fi dystopia. Use cases in ecommerce, particularly, seemed to be widely ignored, although the consumer advantage to pushing out useful image tech for customers would become undeniable.

Were companies waiting in the wings for the right time to launch better automated photo tagging? Had they grown wary of rolling out features in the wake of these missteps? Who would be the first to break the dam?